Partial view of the Port of Rotterdam, The Netherlands © Alf van Beem

There are lots of poems about the sea and sailors. My grandfather was a sailor, as an officer in the British Royal Navy, although I never knew him because he died before I was born. I’ve known others, though, who have sailed the Wild Blue Yonder for a living. As a result, there have been a great many poems written about “life on the ocean waves and a home on the rolling deep”, my personal favourite being Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner”, about the crewman on a whaling vessel who shoots dead an albatross, thus bringing bad fortune (and death, of course) to his ship and all his crew mates. Just goes to illustrate the dangers of crossbows and nautical superstition.

Go back three millennia and the eastern Mediterranean was popular as a watery transport route for such people as the Hittites, the Mycenaeans and the Egyptians, among others, until the waters were overrun by a violent bunch known as “the sea peoples”, which suggests they did quite a lot of sailing, too, in order to get to the places they wanted to attack and rob. Until they were ultimately defeated, this group, whoever they were, attacked the various empires and mighty cities bordering the Mediterranean and, despite ultimately losing, they weakened the naval powers of the large and important nations of that time, which never fully recovered. Although nobody knows for sure the identity of these late Bronze Age marauders, they certainly caused a lot of fear and havoc Seagoing powers of today might be well-advised to look carefully at China and its nautical ambitions, especially if transportation by sea is vital to their economies.

So just what is China up to today? Well, Xi Jinping, who is General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and who has led his country rather successfully since 2012, has ambitions to expand his influence further, and who can blame him? Certainly, China’s maritime influence has been increasing quite dramatically. At the time of Barack Obama’s first inauguration as President, Chinese influence only reached a bare 2% in the world, whereas now it stands at more than 11%, placing China second only to the United States in terms of Overseas Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI). What’s more, in three of the last five years Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to Europe has exceeded the sum invested in the United States. Additionally, China has been buying up European ports, along with political and commercial influence. And why not? After all, three millennia ago the Eastern Mediterranean was already a popular route for anyone who reckoned they could possibly turn a profit there, so there is potential for a well-run China to do so, too.

In 2013, Beijing inaugurated an ambitious and far-reaching project known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), that includes a wide-ranging strategy designed to extend China’s economic reach, investments, and influence westwards, with a particular focus on controlling strategic seaports capable of handling large volumes of trade. Across the Indo-Pacific region, Chinese firms have acquired substantial stakes—and in some cases, complete ownership—of ports that serve both commercial and, potentially, military purposes. This network, often described as a “string of pearls,” stretches across the Indian Ocean, connecting critical maritime bottlenecks like the Strait of Malacca in the South China Sea to the Suez Canal, leading to the Mediterranean.

In Europe, China has already established itself as a major force in the operations of key North Sea ports. For instance, it holds a 35% stake in Euromax, the operator of Rotterdam, Europe’s largest and busiest port. It also owns 20% of Antwerp, the continent’s second-busiest port, and has full ownership of Zeebrugge, the world’s largest roll-on/roll-off vehicle handling facility. These investments are a clear sign of China’s growing influence in global maritime infrastructure.

However, influence doesn’t always require total ownership. Take the port of Hamburg, Europe’s third-largest port, as an example. Here, the volume of Chinese goods passing through exceeds the combined traffic from all other countries. A controversy was sparked in 2017, when China’s Communications Construction Company was awarded a contract to build a new container terminal capable of accommodating Ultra Large Container Vessels (ULCVs). German and other European bidders accused the process of being unfair, highlighting the tensions that can arise as China expands its presence in critical global infrastructure projects. This mix of investment, trade dominance, and strategic port acquisitions illustrates the ways in which China is becoming a key player in global trade and international politics.

The European Union has stepped up its measures aimed at excluding Chinese investment from Europe’s ports, although results suggest that Europe has benefitted from them. Research shows that European ports benefitting from Chinese investments saw increases in their container shipments, not only with ports in China but also with ports in other countries. Ports that have benefitted especially include those of Piraeus, Antwerp, Rotterdam, Barcelona and Le Havre. Other research has shown that inward investment from China has helped to rebalance shipping activities in Europe to the advantage of Mediterranean ports which have developed into transshipment and gateway hubs with heterogeneous profiles (that’s what the report says, anyway). Attempts to stem this source of inward investment would cost Europe dearly and hamper the growth of its ports.

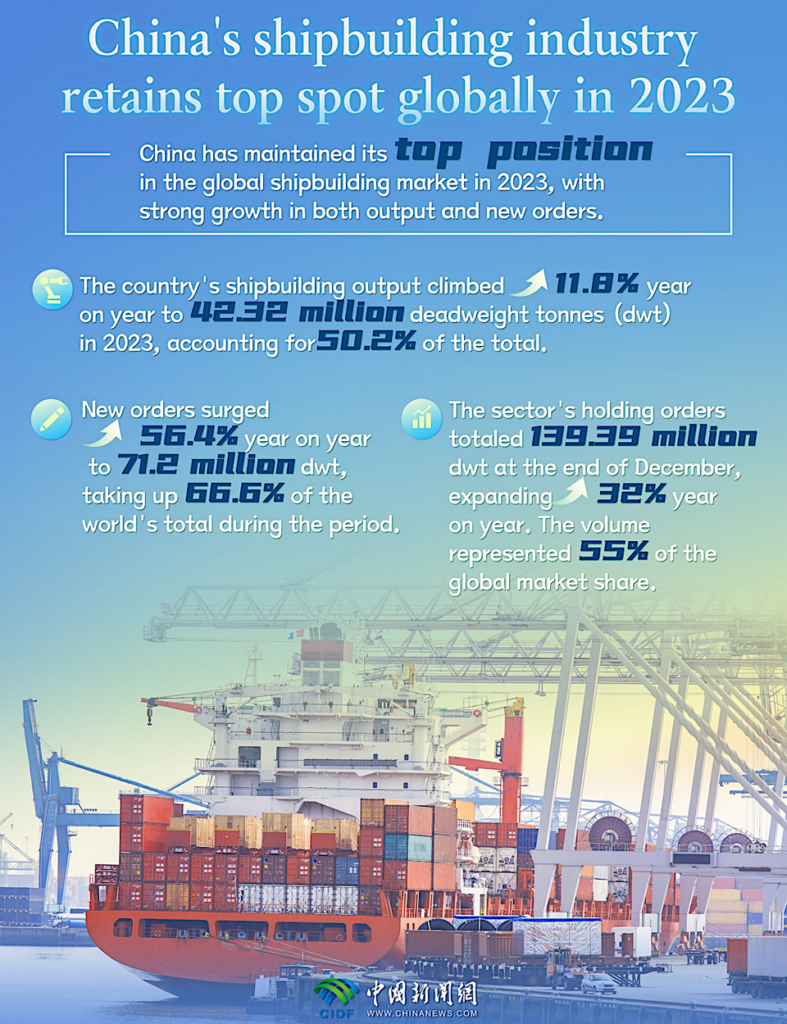

When we talk about the countries that host seaports, it’s clear that the benefits of Chinese investments go far beyond just the immediate economic and political gains that come from partnering with one of the world’s leading economies. China’s influence in the global seaport industry is nothing short of remarkable. Over the past twenty years, China has dominated the world in the trade of goods, and its container handling capacity have ranked at the very top in global terms. In fact, when you look at the list of the world’s top 20 ports in terms of trade flow or container handling, 13 of them are located in mainland China. This isn’t just a proof of China’s economic might—it’s also a reflection of how critical these ports have become to the global economy.

One of the key players behind China’s growing presence in the global port industry is China COSCO Shipping. This giant shipping company, which started as a state-owned enterprise in 1961, began making its mark internationally in the late 1980s. By 2000, it had become the first Chinese company to join the World Economic Forum, a clear sign of its rising global influence. Over the years, COSCO has invested in numerous ports around the world, and its strategic partnerships have been crucial to its success. For instance, its connection with ONE, one of the three major container shipping alliances, has been a game-changer. Allowing a carrier like COSCO to have a stake in a container terminal is one of the best ways to ensure that the port attracts more ships and higher volumes of cargo. Today, alongside China Merchants Port—another major Chinese maritime financial group—COSCO handles roughly 24% of the world’s total container capacity, measured in TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units). That’s a massive chunk of the global market.

In Europe, China’s presence in the port industry spans seven countries, with Germany standing out as its main European partner. The trade volume between China and Germany alone is staggering, amounting to nearly €300 billion annually. What’s interesting is how China has approached its investments in Europe. In most cases, it has acquired minority or majority stakes in container terminal operations, rather than outright ownership. The exception to this rule is Greece, where China was given the unique opportunity to purchase a majority stake in the managing entity of the Port of Piraeus. This deal has allowed China to play a decisive role in shaping the port’s present and future, making it a standout example of Chinese influence in European maritime infrastructure.

Since 2008, the volume of containers handled there has skyrocketed to record-breaking levels, and its connectivity within the liner shipping network has grown exponentially. Today, Piraeus isn’t just a port—it’s a major transhipment hub, a busy gateway that connects Europe, Asia, and beyond. In fact, it’s now the fifth-largest container port in all of Europe, trailing only behind giants like Rotterdam, Antwerp-Bruges, and Valencia. And if we narrow our focus to the Mediterranean, Piraeus holds the third spot, right after Valencia and Tangier Med in Morocco.

What’s particularly interesting here is the role of Chinese investments in this success. It’s not just Piraeus that’s seen Chinese involvement—every single one of these major container ports, from Rotterdam to Valencia to Tangier Med, has benefitted from Chinese capital and expertise. This isn’t a coincidence; it’s a clear reflection of China’s strategic vision to embed itself in the global shipping network. By investing in these key ports, China isn’t just boosting its own trade capabilities—it’s also helping to modernise and expand critical infrastructure that keeps the world’s economy moving.

All of this highlights just how intricately connected China has become to the global port industry. It’s not just about money or trade—it’s about building connections, forging alliances, and creating a network that spans the globe. For the countries hosting these ports, the benefits are clear: access to one of the world’s most dynamic economies, increased trade volumes, and a stronger position in the global market. And for China, it’s a strategic move that solidifies its role as a key player in shaping the future of global trade.

As far as other parts of the world are concerned, it’s truly staggering to see how far-reaching China’s influence has become. Take, for instance, projects like the Melaka Gateway in Malaysia and Port Darwin in Australia—both of which are key examples of China’s strategic investments in maritime infrastructure. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. If we zoom in on the Bay of Bengal, we see a strong Chinese presence in countries like Myanmar, where they’re involved in the Kyaukpyu port, as well as in Sri Lanka, where they’ve played a major role in developing Hambantota and Port Colombo. Over in Bangladesh, the bustling Chittagong port also bears the mark of Chinese investment and expertise.

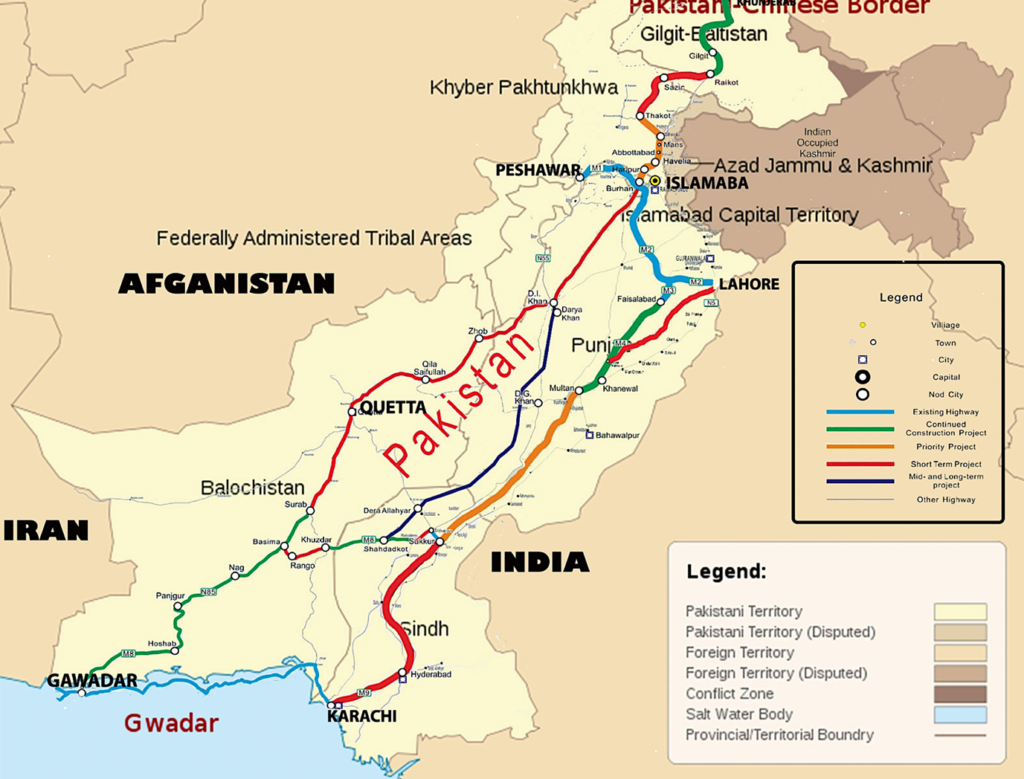

Moving over to Southwest Asia, the list of Chinese-backed port projects grows even longer. In Pakistan, the strategically significant Gwadar port is a cornerstone of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Over in the Middle East, China has made its mark in Saudi Arabia with Jeddah Port, in the UAE with Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi, and in Oman, where they’ve also established a presence.

Heading down to Eastern Africa, China’s footprint is equally impressive. Countries like Kenya, Sudan, and Tanzania have all seen significant Chinese involvement in their port infrastructure, helping to boost trade and connectivity in the region. Over in the Maghreb, nations like Algeria and Morocco have also welcomed Chinese investments in their ports. And if we look at the non-European Mediterranean, the story continues—from Egypt, where China is involved in ports like Damietta and Suez, to Turkey, where they’ve made strategic moves in Kumport.

What’s fascinating here is how these investments aren’t just about building ports—they’re about creating a vast, interconnected network that ties China to some of the most strategically important regions in the world. For the countries involved, these projects often bring much-needed infrastructure development and economic opportunities. But for China, it’s about becoming an important part of global commerce, ensuring that its influence is felt far beyond its own shores. It’s a bold strategy, and one that’s reshaping the world’s maritime landscape.

Meanwhile, the tariffs being imposed by the Trump administration will have global repercussions, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), largely because of the 20% increases in tariffs imposed by the United States on imports from China, which have in turn led to retaliatory action on the part of Beijing. Trump’s new tariffs, according to the OECD, will slow growth in China but also in several other places. The OECD predicts that China’s economy will grow by 4.8% this year, slowing to 4.4% next year. The OECD blames this on the increase in US tariffs and the resulting if inevitable repercussions. Some experts have predicted this skirmishing with economics could lead to a protracted trade war that nobody seems to be addressing or even showing a potential interested in trying to address.

Inevitably, Europe gets caught up in this complicated and stupid game. China is, after all, one of the EU’s largest trading partners after the United States, although the absolute volume dropped in 2023-24. Even so, China was the third largest partner for EU exports of goods, taking 8.3%. Imports have recently declined, but at 21.3% are still well ahead of the United States on 13.7%. According to the EU, it views China as “a partner for cooperation, an economic competitor and a systemic rival”, and there is concern in Europe over the systemic imbalances that characterise China’s economy. China’s industrial policies have been described as unfair in competitive terms, “with what Europeans view as unfair support for the manufacturing sector”, while some say European businesses cannot compete fairly because the playing field is too uneven. Another aspect that worries Europeans is that China seems to be increasingly determined to be self-sufficient. In January 2023, EU exports to China stood at €19.2-billion, falling to €16.8-billion by December 2024. Is it a pattern or just a natural fluctuation? Looking at imports from China, they stood at €46.4-billion in January 2023 but had dropped to €35.6-billion by January 2024. As I recall from my economics lessons very many years ago, fluctuating figures for imports and exports among trading nations tended to reflect the fast-changing politics of the time. They still do.

Even so, a number of European companies seeking to compete with Chinese rivals have argued that China’s business environment has become too “politicised”, which probably doesn’t surprise you. They also say that there has been no easing of the various regulatory obstacles that exist, while there is (they say) a complicated and “non-transparent” legal framework on cybersecurity, as well as restrictive rules on the cross-border flow (or leak, in some cases) of data. Even so, and despite these many and varied obstacles, the EU says it’s committed to “de-risking” in its dealings with China, not cutting itself off.

Trade between the two remains important for both, and that means trade in many different commodities, from agricultural produce and raw materials, such as chemicals and naturally-occurring minerals, to manufactured goods. EU officials are finding it much harder to do business with a United States headed by Donald Trump, who has threatened to put a 200% tariff on all wines, champagne and alcoholic products originating in the EU. This is unlikely to go down well with America’s billionaires, who seem to be very influential, but EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has already threatened to impose tariffs worth €18-billion on exports from the United States. Perhaps with so much arguing and bluster between the sides, someone should invent a board game about it, although the name “Monopoly” has already been taken.

As the European Commission proudly boasts, “For Europe, maritime transport has been a catalyst for economic development and prosperity throughout its history.” It would not help to interfere with that. It is, of course, why China is so interested in investing in Europe’s mercantile ports. More than 80% of the world’s merchandise is transported by sea, so maritime transportation remains the backbone of trade globally. Some EU experts fear that the risks of heavy Chinese investment in nautical transport around Europe are too little understood and could pose a risk. Some fear that financing investment with loans under China’s Belt and Road” initiative would give China considerable leverage over future directions and policy decisions. The idea, adopted in 2013, would give China influence in some 150 countries, especially if it provides the finance to the various countries involved as loans. It’s been suggested (not unreasonably) that it’s really a response to the US “Pivot to Asia” policy and a bid to gain the initiative. China’s biggest investment so far in this policy (at the time of writing, at least) has been $62-billion (€57,305,290,014) for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which is in fact a collection of various related projects linking China with Pakistan’s Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea. China is thought to have spent an estimated $1-trillion (€0.92-trillion) on this project alone, although experts say Chia’s costs over the entire project could reach $8-trillion (€7,388,282,409,600.00).I must confess, not being a mathematician, that I find quite so many zeroes quite incomprehensible and beyond the grasp of my brain, whether they’re in dollars, euros or plastic ducks.

If the result turns out to be the modernisation of commercial ports and the mechanics of handling a throughput of merchandise in each, then there is no perceivable downside to Chinese investment. But things are never that simple, of course. It could mean that everything in each port is owned by the Chinese government, who can then control exactly what goods and in what quantities are allowed to pass through. That’s a different story, of course, because it would mean that Beijing would be in total control of all mercantile sea traffic, deciding exactly what goes where, for how much money, and what China could extract in return. It would mean that all world trade would be entirely at the whim of whoever is in power in Beijing.

Of course, China’s motivation (other than sheer naked power) could be to boost China’s global economic links to its western regions, thus also promoting economic development in the western province of Xinjiang, where there have been outbreaks of separatist violence. That is certainly one powerful motive, along with making sure of long-term energy supplies from Central Asia and the Middle East along routes that would be immune to American interference, should any be attempted. Alternatively, a more generous interpretation could be to promote the more assertive China under Xi, who wants to make China a central and pivotal player in global affairs. China has already achieved a lot under Xi’s leadership, and it seems likely that future maps of world trade could place Beijing at the centre, rather than Washington (or Brussels, of course). China has been taking some massive economic risks to raise its mercantile profile, its outstanding loans coming to more than 25% of its gross domestic product. That’s daring, especially in today’s explosive and somewhat unpredictable world. China is driven by its geopolitical and economic motives, so it has taken great courage, as well as great ambition, to get to where it now finds itself. But if it all works out as Xi intends, then history may record the 21st century as being China’s. Only time will tell, but so far Xi has not demonstrated a desire to own the world. Unlike Moscow and Washington, he has not talked of wanting to conquer or take over any foreign countries. If he’s simply out to make a profit without a war and without harming anyone, as he claims, I can only wish him luck.

In any case, Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative seems to be selling itself, with 147 countries – that’s two-thirds of the world population – having already signed up to its various related projects or expressed an interest in doing so. Certainly, it serves as a poke in the eye for Trump’s “Pivot to Asia” project, as China seeks out and secures new trade linkages and develops new export markets for China ‘s many goods, which it is inclined to over-produce so that it needs profitable ways to dispose of it all. Certainly, today’s busy, bustling China under Xi’s leadership, has already established itself as a strong and ever-stronger power in the world. As it is, as long as Xi’s motives are shown to be innocent (assuming they are) then all I can say is “祝你好运,祝地球好运 or Zhù nǐ hǎoyùn, zhù dìqiú hǎoyùn. It means: “Good luck to you. Good luck to the earth”. We may need it.