Instead of a wine that makes you sleepy, imagine one that could keep you up and talking all night. Imagine again that this wine, far from being bad for you, was in fact a health tonic with innumerable and immediate benefits. These were claims of the producers of Vin Mariani, a French drink that, in the late 19th century, sat on the desks of popes, writers, and even royalty. What was its secret and why, since it was so popular, have we not all heard of it? The answer lies in its secret ingredient: Peruvian coca, the Andean plant from which cocaine is produced.

Crazy for Coca

The latter half of the 19th century was a golden age for Western botanical developments. Pharmaceutical firms, patent medicine makers, and remedy manufacturers scoured the globe for plants that could be marketed as miracle drugs. Coca, long used in Indigenous Andean cultures, became the poster child for a new kind of invigorating medicine.

“It was immensely popular with a particular sort of ‘sophisticated’ consumer,” according to Joseph Spillane, History Professor at Florida University and author of Cocaine: From Medical Marvel to Modern Menace.

Western society was increasingly interested in stimulants, and coca fit the bill: an energising, endurance-boosting plant that seemed perfect for the age of industrial progress. But coca was not just sold as medicine. Vin Mariani was marketed as an all-purpose tonic, a fashionable elixir promising vigour, vitality, and mental sharpness. Unlike modern pharmaceuticals that targeted specific ailments, coca-infused tonics were marketed as general restoratives—good for anyone feeling tired, weak, or overworked.

In High Society

Among all the coca-based products, Vin Mariani stood at the top. Invented in 1863 by French chemist Angelo Mariani, the drink infused coca leaves in Bordeaux wine, creating a luxurious and mildly intoxicating tonic.

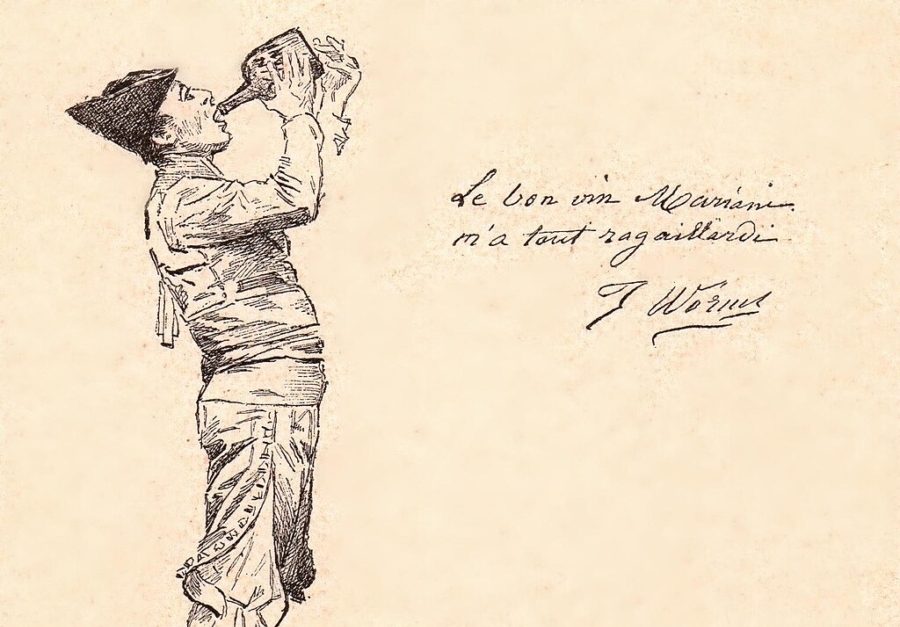

“Vin Mariani was the subject of really remarkable advertising campaigns, which deployed the endorsements of the famous and notable from around Europe and North America,” Spillane said to TalkingDrugs.

Vin Mariani’s list of enthusiasts reads like a who’s who of the 19th century: Thomas Edison, Émile Zola, and even Ulysses S. Grant all praised its invigorating effects. Pope Leo XIII reportedly carried a flask of it and awarded Angelo Mariani with a gold medal for his invention.

The Making of an Icon

While Vin Mariani was dominating the European market, coca-infused tonics were also becoming popular in the U.S. But the landscape was about to change.

One of the biggest turning points came in 1886 when John Pemberton created Coca-Cola. Originally designed as a non-alcoholic alternative to coca wines, Coca-Cola capitalised on the coca craze—but without the intoxicating effects of alcohol. The drink’s early formulations still contained coca leaf extract – specifically ecgonine, an alkaloid from the plant – and its branding as a health tonic mirrored the strategies of Vin Mariani.

However, coca would not dominate for long. As Spillane noted, cocaine quickly overshadowed coca in the Western market. While coca was seen as a crude, unscientific plant, cocaine—its isolated alkaloid—was hailed as a breakthrough drug. Cocaine was used in medicine, dentistry, and psychiatry, and was seen as more modern, more effective, and more precise than coca leaf tonics. Sigmund Freud was one of cocaine’s earliest and most vocal advocates, hailing it as a miracle drug that could cure depression, enhance energy, and even combat morphine addiction. In his 1884 paper Über Coca, he extolled its virtues with near-religious zeal, calling it “a magical substance”— but this enthusiasm was not destined to last.

Another Moral Panic

By the early 20th century, the reputation of cocaine had plummeted. Reports of overuse, addiction, and racialised fears about cocaine-fueled crime began to dominate public discourse. As cocaine became linked to criminality and addiction in the public consciousness, it dragged coca down with it. Coca, despite being distinct from pure cocaine, was caught in the crossfire.

“Both reputationally and through the passage of anti-cocaine legislation that restricted coca, the market in coca wines collapsed,” according to Spillane.

Coca-Cola, sensing the change in public perception, switched to “de-cocainized” coca extract, stripping the plant of its active alkaloid. By the 1920s, the golden age of coca tonics was over.

“From 1884—the year that cocaine first exploded in Western medicine—and for the next maybe two decades, coca lacked lustre because it was not cocaine. Then, interestingly enough, by the early 20th century, coca lacked lustre because of its association with cocaine!” Spillane said.

The View from the Andes

Despite its rapid disappearance from Western markets, coca remained deeply rooted in Andean cultures. But as Paul Gootenberg, described in his book Andean Cocaine, even in coca-producing nations like Peru, early elites dismissed coca as a “backward” Indigenous practice. Ironically, they embraced cocaine as a symbol of scientific modernity.

However, the subsequent prohibition of cocaine—and with it, coca—hit producer nations hard. Coca farmers, who had grown the plant for centuries for traditional and medicinal use, suddenly found themselves at odds with international drug policies. Instead of supporting a regulated coca market, prohibition led to criminalisation and violent coca eradication campaigns.

In La Paz, Bolivia, up a cobbled alleyway just off of the Witches Market, lies the Museo de la Coca; the Museum of Coca. A passion project of the museum’s proprietor, it occupies an old, slightly dark building tucked away where you might not expect to find it. Inside are countless exhibits on the history of coca, both commercial and traditional. There are dusty bottles of original Coca-Cola and Vin Mariani tucked next to scientific studies on the benefits of ingesting natural coca. It’s clear what the owners of the museum think about the plant’s prohibition, and based on the profusion of products for sale nearby, clear what most people in producer nations think too.

A Curiousity Comeback

Despite its long exile from Western shelves, coca is making a quiet comeback. In South America, countries like Bolivia have fought for the decriminalisation of coca, having left the UN drug control conventions in 2012, re-accessing a year later with an exception to allow for domestic coca chewing and a market to flourish.

Back from the dead, Vin Mariani itself has seen a recent revival. The recipe was not passed down by the original creators, however, it was relaunched in 2014 by Christophe Mariani (no relation to the original family), using the same method of “de-cocainised” coca that Coca-Cola employs. Christophe even met with ex-Bolivian President Evo Morales about producing Vin Mariani in his country.

Spillane argues that there is no legitimate reason for coca’s continued prohibition—especially considering its historical popularity and the scientific evidence suggesting it is far less harmful than feared.

“Suffice it to say that coca was always collateral damage in the fight against cocaine. No one was specifically campaigning against coca, it was just something that had to go to assure that cocaine would go.”